Galt High explores future steps in response to poor student diagnostic scores

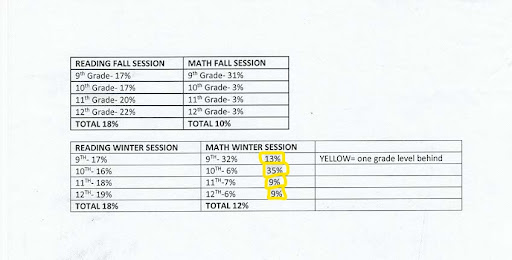

Data table showing the percentage of students at grade level for each class for the I-ready diagnostic test, courtesy of Principal Kellie Beck, Galt High School.

January 2, 2023

Following poor results from the fall session of the I-Ready diagnostic, Galt High School officials decided to offer significant incentives to students who tested at grade level in hopes that the winter session might yield better results – but whether or not they worked is questionable.

Data from both the winter and fall sessions for the I-Ready show no change in the combined reading score for all four grades, and a slight improvement in the combined math scores. A vast majority of each class remains below grade level in both math and reading, with math scores being the category that is lowest. While math scores improved for each grade between the fall and winter sessions, reading stayed the same for freshmen and went down for every other class.

Based on the data, freshmen had the highest math scores in both the fall and winter sessions, with sophomores, juniors, and seniors falling far behind.

The I-Ready diagnostic is a test administered to mark student growth and monitor progress.

However, a large problem with the test is that it doesn’t account for the variances in scores based on student motivation level, said Galt Joint Union High School District director of educational services Sean Duncan.

“I think we need to make sure that the data we’re getting is accurate,” Duncan said. “And that was the challenge is that when we look at the students that are underperforming, we always have the question, why are they underperforming? Because they need help? Are they underperforming because they’re not motivated?”

Duncan illustrated his point this way: “Let’s say an AP student takes the exam and they end up getting far below, we know that that’s a motivation issue – the student’s not interested in taking it.” He added, “. . . if we can fix the non-motivated student problem and say, no, everyone that took the test took it seriously, then we know the data is 100% accurate and then we can really act on it. So we’ve had a lot of conversations this fall with both Mrs. (Kellie) Beck and Mr. (Joe) Saramago over at Liberty Ranch around how do we incentivize (and) how do we motivate kids to take this a little more seriously, so that the data we’re looking at is accurate.”

In an effort to counter the lack of motivation, GHS has offered a multitude of incentives and attempted to get parents involved, Beck said.

Among the incentives: off-campus lunch passes for more than the regular Tuesday and Thursday for those who tested at grade level; sending out each student’s scores to their parents to encourage accountability; posting a Top 10 list for the highest-scoring students in each class; and giving students who tested at grade level the choice to not take the diagnostic again in the Spring.

Aside from the motivation issue, GHS principal Kellie Beck pointed to graduation requirements as another problem, particularly for math scores.

“One thing we noticed, too, (that) is a problem is when you’re in 11th and 12th grade, a lot of these kids stop taking math because it’s not a requirement,” Beck said. “Our graduation requirement, if you just want a minimum, is two years of math. … It’s recommended three or four years of math, but a lot of kids don’t (take that) and that really hurts us when they take the test. If you haven’t had math in two years, your skills are not going to (be as sharp).”

The problem with graduation requirements is yet another result of the COVID pandemic and state law, Duncan said.

“The goal was that … 2020 was going to be the first year that students had to graduate with 280 credits and three years of math,” Duncan said. “But because COVID happened, we didn’t make the decision to reduce graduation requirements at that time, the state forced us to. We didn’t think we had to because we were so close to the end, we closed in March, we had computers and everything in everyone’s hands a few days later, and we only had a couple of months left. We thought we could have made it – but the state said no, you have to.”

Another important issue, according to Duncan, is the correlation between students’ classroom performance and test results.

“When we look at the data on the tests, and we compare it to grades, we see a very direct correlation that students in general that do poorly on the tests are also suffering in their classes,” Duncan said. “They’re not doing a good job in their classes. There is a problem there that we need to address.”

Results from previous diagnostic tests have already played a role in addressing this problem, Duncan said.

“Assuming that some of that data at least is accurate, the next question is really how do we intervene?” Duncan said. “So we’re looking at, like, what classes do we offer? So this year is the first year at Galt High School that we have offered a Math Foundations class. And the reason for that is … the research shows that by placing kids in Integrated Math 1, even if they’re not fully prepared, but then providing them scaffolds, they’re going to be more successful and they’re going to accelerate faster, so you’re gonna see more growth.”

Beyond simply helping with math scores, the district also has taken steps to give students more resources to grow in both fields, Duncan said.

“So how do we help them?,” Duncan said. “Like I said, we have tutoring (both in person and an online service called Paper), but also working with teachers and providing strategies and professional learning. Because what our teachers are used to teaching is the content that they know, but many of our students we (have) now have a two-year gap (because of COVID). So there’s been a lot of professional learning and opportunities that we’ve done over the past year, year and a half, to try to help teachers with that.

“We’re also in the process of adopting a lot of new textbooks that have a lot of support strategies built in.”

One of the main areas of concern for the GHS administration and teachers should be to improve the performance of students who are just below grade level but need a little extra help, Beck said.

“So with a little bit of push and more instruction, we can get them to the next level and they would be at grade level, so to me that’s the promising piece of it,” Beck said. “These guys eventually could be in this category, so you can see how big that number would be.”

GHS leadership and AP World History teacher Megan Piper-Ehnat said, regardless of all the steps being taken to improve the current system under the administration of the I-ready test, using the test to monitor progress doesn’t account for the complexities of students’ lives.

“(It) doesn’t take into consideration relationships, or whether you just woke up and had a bad morning and therefore you’re not going to test well that day,” Piper-Ehnat said. “Which we talked about a lot. I mean, especially as an AP teacher too, we talk a lot about how teaching to the notion of a test is such a broken system these days. Because when we take tests, we see the results and we say, ‘Oh my god, I’m that test score,’ – but that’s not true.”

One of the obstacles in adapting a better system has to do with where the funding for the school comes from, Piper-Ehnat said.

“The hard thing is, I think we’re bound to certain things that we have to do, because we are a state-funded public institution,” Piper-Ehnat said. “But the hard thing is … I don’t know that testing is… the best way that we can gauge where (students) are at anymore.”

Among students, the consensus is that the I-Ready test isn’t a terribly helpful tool.

“I-ready itself is just a waste of time in my opinion,” sophomore Aydin Interiano said. “Instead of learning about math for a day, you can just be stuck guessing on a test that has no real impact on your grade, and just gets the school more money.”

Older students also see the test as a waste of time, especially considering how far they are along their high school journey.

“I felt less motivated to complete (the I-ready) due to the length of the test as well as not having proper incentives to complete it,” senior Keylend Brooks said. “But I was also indifferent because it doesn’t do anything for me as a senior and felt like a waste of the day.”

Duncan noted the I-ready is a recent development, explaining GHS started using it in 2020, when the Covid-19 pandemic forced the district to find alternatives to its previous tests.

While GHS may have a ways to go before it can claim mastery over the I-ready, Duncan said GHS remains committed to providing the best possible educational outcome for students.

“On average, students who graduate with four years of English and three or four years of math are going to end up in jobs that get (them) paid higher salaries,’ Duncan said. “And that’s what we want. We want our students to be successful, go out, make money and have a nice life, right?

“So that’s our goal, and that’s what we’re trying to do – and that’s how we’re trying to use the I-Ready to guide those discussions.”