Should California students be “tracked” in math?

Concern that common level could hold back advanced students

California’s Instructional Quality Commission is considering a rewrite of the California Mathematics Framework that would, among other things, recommend that all students take the same set of math classes until 11th grade, eliminating accelerated classes until then.

This has proven to be hugely controversial. While the change is meant to address the fact that a majority of students are not meeting grade-level expectations, as well as racial inequities in advanced math courses, it has faced pushback from teachers and parents of “gifted” students who are not challenged by traditional math courses.

Many teachers and parents are concerned that putting all students together in one grade-level math class would hinder the progress of students with natural abilities in math. “Math tracking,” as it is called, can allow for mathematically adept students to face greater opportunities for success, and be intellectually stimulated where they otherwise may not be.

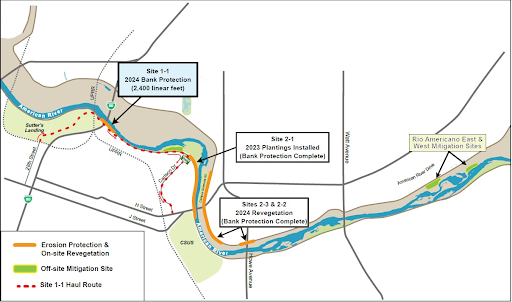

“If you’ve got a kid that’s taking Calculus as a freshman, he probably is an exceptional student, and it would benefit him to move forward more quickly,” said Todd Freund, who teaches Integrated Math 2 and Precalculus at Rio Americano. However, Freund sees this case as a rare exception. “I don’t think there needs to be a hurry for almost all students. There should be an occasional exception for an [advanced] kid but I think we make that exception too much,” he said.

Although the framework change would still allow students to take accelerated courses such as Calculus after tenth grade, some are concerned about the need for completion of advanced math courses in order to pursue a college degree in STEM careers. “I think in the long term, you’ll have less students who go into STEM fields,” said Rio Integrated Math 2 and Calculus AB teacher Dag Friedman.

The change is intended to help the large number of students who seem to be getting left behind when it comes to math. It cites the concept of “giftedness” as potentially harmful to students’ confidence and motivation in the subject.

“Particularly damaging is the idea of a math brain, that people are born with a brain that is suited (or not) for math,” the rewrite says.

The San Francisco Unified School District, which voted in 2014 to eliminate accelerated math classes until high school, saw significant improvement in math performance five years later. Algebra 1 repeat rates decreased from forty percent to eight percent for the graduating class of 2019, and thirty percent of all the high school students were taking courses beyond Algebra 2. Whether the bill would have the same effect in the rest of the state remains to be seen.

“I’m conflicted,” said Freund on whether these advanced courses should continue. “I do want [exceptional] students to be able to accelerate forward, but I do think there’s a push by most parents to try to push their kids forward too much and as a result it’s unhealthy.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Student Education Reporter program. Your contribution will allow us to hire more student journalists to cover education in the Sacramento region.